For the past two weeks, I’ve been watching nothing but the Tolkien films. This occurs occasionally, in my Arda-saturated world. The tales JRR Tolkien shared with the world are as ingrained in me, in my soul, as they are in anyone who has ever been moved by a myth or a legend. These are stories as old as time, at least as it is perceived by humankind. You can call it ancestral memory, cellular memory, genetic memory, whatever it is, the remembering experienced by people when immersed in the epic accounts of a nation or race is what drives every generation to redefine the stories to fit their times, and to make sense of the world in which they find themselves.

On the recommendation of my sixth grade English teacher’s son, who was a year my senior, I checked out The Hobbit from the school library, and absorbed it in three days. Before I returned it to school, I read it again, this time more slowly, taking a week. I loved it, but hated the musical abomination that was the Rankin-Bass adaptation. Normally, I loved their TV specials. Not so with their version of The Hobbit. I did, however, love Return of the King, primarily because of Glenn Yarbrough's beautiful song, "Roads Go Ever On."

Even though I had loved the book, it didn’t compel me to pick up The Lord of the Rings, which Gregg also recommended, or The Silmarillion, of which I doubt Gregg was aware, based simply upon his age and how difficult it was to be privy to information, literature, music - basically everything - that wasn’t in the realm of the commonplace. LOTR and The Hobbit were popular enough to be well-known and easily-obtainable in the South. The Silmarillion, on the other hand, had only been published for approximately two years at that time. Even if Gregg knew about it, it was highly doubtful the school library had book!

On the day I took my SAT, in my senior year of high school, Aunt Tudi found a box set, which I still have, of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit at a yard sale she and Granny visited while they waited on me to finish my test. I still did not read LOTR. I was busy with other things at the time, like getting through my last year in high school, preparing for college, and writing this odd collection of mythic stories that were born out of my lighthearted science fiction shorts, originally inspired by the Electric Light Orchestra’s Time album.

In my first year of college, my Humanities professor was impressed with my assignments and asked if I was a writer. I told him I wrote stories and poetry, and had been active in the literary and drama clubs in high school. He asked to see some of work, so I opted to share with him some of the stories of the Rhyllans, and how they came to be.

A week later, Dr. Miller, who happened to be a Tolkien scholar who had taught classes on the old professor's works, asked if I had read The Silmarillion. When I asked why, he informed me that I could be sued for some of the material I had written, if I ever tried to clean it up and get it published. I did not understand but, instead of reading The Silmarillion, I opted to read The Lord of the Rings, under the incorrect assumption that it came before The Silmarillion. Publishing-wise, it did, but I was thinking of the timeline of the narratives themselves.

Of course, I fell in love with The Lord of the Rings, and promptly went to B. Dalton Books and purchased a copy of The Silmarillion, which I still have. When I read the Ainulindalë and Valaquenta, I finally understood Dr. Miller’s warning, and I reconciled with the fact that my Rhyllan myths would never be published in any complete capacity. The one thing I couldn’t understand was why I was unable to make myself change much of anything in my myths, even though their current incarnation would get me chased around by the Tolkien posse.

Of course, I fell in love with The Lord of the Rings, and promptly went to B. Dalton Books and purchased a copy of The Silmarillion, which I still have. When I read the Ainulindalë and Valaquenta, I finally understood Dr. Miller’s warning, and I reconciled with the fact that my Rhyllan myths would never be published in any complete capacity. The one thing I couldn’t understand was why I was unable to make myself change much of anything in my myths, even though their current incarnation would get me chased around by the Tolkien posse.

This is where I want to make it very clear that I am, by no means, comparing my writing to that of JRR Tolkien’s, who far surpasses the greatness of the likes of Clive Barker, and he greatly surpasses even my wildest dreams of scribal skill. The essence of the stories, in particular the Music of Creation and the diminishing of the Dėaghydge, was exceedingly Tolkienesque. Even the Goddess Kessilon, the Dėaghyden Star Goddess, was nearly identical to Varda, albeit a tad more sci-fi in her relationship to the stars. My mind was boggled, and it still is, even though I came to learn the root of the similiarities.

It wasn’t until three years later, when I began to study theology and various theories, one of which was genetic memory, that I understood the connection between my stories and those of JRR Tolkien’s. It wasn’t a connection that involved just myself and Mr. Tolkien; it was one that encompassed a great swathe of the Fantasy literary world and the whole of human myth, be it supposedly dead myths of ancient Greece and Sumeria, or the living religions like Hinduism and Judaism. They are all retellings of a very tiny collection of stories that speak of humanity’s commonality. And the connection doesn’t affect just nations or tribes, or even families; they affect individuals. We all have the capacity, and often the compulsion, to create our own personal myths. This is what I was doing with the Rhyllan folk, and their sister races, the Tarmi and the Thranodiena ~ all three of whom comprised the descendants of the divine Dėaghydhe.

In 1993, I was tasked with deciding on a Craft name, because I had decided to become a Dedicant in the Temple Hecate Triskele. I opted for Tinhuviel, adding the “h” for numerological purposes. Artanis was a name for the Tarmian Goddess of the flora and fauna, tightly connected with bears, owls, and lizards. It wasn’t until about a year later, I discovered that Artanis is also Galadriel’s father-name! So this is why I feel that Tolkien’s works aren’t simply fiction. They have an ancient magick within them. They have the power to bring people together and, sadly, because of their religious nature, they also have the power to pull them apart. Such is the way with spiritual works. JRR Tolkien wanted to create a mythology for England. He certainly did that, but he did so much more. He enriched the mythologies of people around the world, so much so, that scientists have named an entire ancient human race after one of his own. That speaks volumes to me, and it should to any student of JRR Tolkien’s work, or human memory in general.

I know it’s an impossibility, but I would love to know the origins of the stories that are obviously of such great import to our species, that they have been retold for thousands of years, and are as beloved today as they were from time immemorial, with no small thanks to JRR Tolkien.

Since I went into seclusion over Smidgen's death, so much bullshit has happened, I just don't know how to properly process it in an acceptable word format. I've been reduced to forwarding news stories and memes, and posting brief interludes of shock and horror at the dismantling of my country. Now, I could share everything I post on Facebook here, but I don't know if that would be something people would want to see, so I leave it to whomever reads this. Do you want me to rant and rave in images and micro-blogs here on the Cliffs, or shall I reserve that for Facebook and Twitter?

Since I went into seclusion over Smidgen's death, so much bullshit has happened, I just don't know how to properly process it in an acceptable word format. I've been reduced to forwarding news stories and memes, and posting brief interludes of shock and horror at the dismantling of my country. Now, I could share everything I post on Facebook here, but I don't know if that would be something people would want to see, so I leave it to whomever reads this. Do you want me to rant and rave in images and micro-blogs here on the Cliffs, or shall I reserve that for Facebook and Twitter?

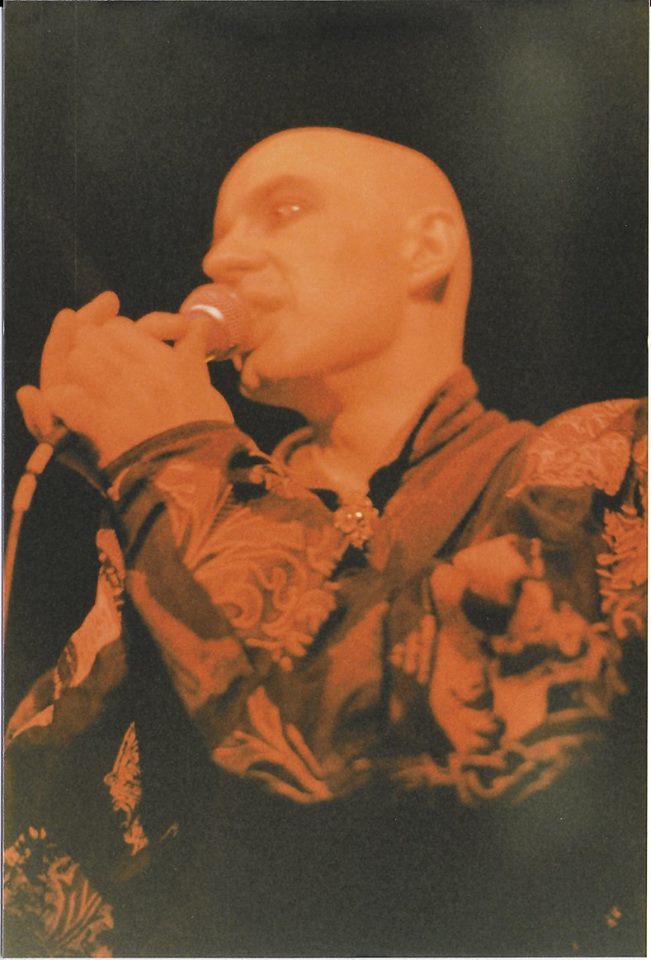

He gave Cadmus his looks. Aunt Tudi thought Barry had the most angelic face she’d ever seen. That, combined with a half-sleep nightmare that involved him, heavily influenced Cadmus’ appearance and dichotomous demeanour.

He gave Cadmus his looks. Aunt Tudi thought Barry had the most angelic face she’d ever seen. That, combined with a half-sleep nightmare that involved him, heavily influenced Cadmus’ appearance and dichotomous demeanour. This was an odd one, because Cadmus was already fully-formed and developed by the time Tom Hardy railroaded into my world. I see my stories as movies in my head and, before Mr. Hardy, Cadmus’ appearance was a very effeminate, Egyptian, alien version of Barry Andrews. Then I saw Star Trek: Nemesis (aptly named) and beheld one of the best actors to come along in a very long time accurately interpret the ravages of child abuse on a young adult, and BOOM, he was anchored to Cadmus. As a result, Cadmus adopted a more sullen affect, at times, and was also graced with an eloquent viciousness, devoid of any bothersome conscience, because conscience was for the weak. Tom Hardy also allowed Cadmus to properly express anger with dignity, inadvertently contributing what I called his “crazy eye” to my character. Cadmus’ change of mood, indicated by just a single subtle expression, can turn a situation of civility into one of slaughter in literally the blink of an eye.

This was an odd one, because Cadmus was already fully-formed and developed by the time Tom Hardy railroaded into my world. I see my stories as movies in my head and, before Mr. Hardy, Cadmus’ appearance was a very effeminate, Egyptian, alien version of Barry Andrews. Then I saw Star Trek: Nemesis (aptly named) and beheld one of the best actors to come along in a very long time accurately interpret the ravages of child abuse on a young adult, and BOOM, he was anchored to Cadmus. As a result, Cadmus adopted a more sullen affect, at times, and was also graced with an eloquent viciousness, devoid of any bothersome conscience, because conscience was for the weak. Tom Hardy also allowed Cadmus to properly express anger with dignity, inadvertently contributing what I called his “crazy eye” to my character. Cadmus’ change of mood, indicated by just a single subtle expression, can turn a situation of civility into one of slaughter in literally the blink of an eye. Annie Lennox

Annie Lennox Pinhead

Pinhead

The old man spoke of Hell in the after life, delighted in promising Cadmar an eternity of what the Elf already had a bellyful of on Earth. But Cadmar did not believe him. Cadmar was learning that you create your own hell, just as you create heaven, right here, right now. And he believed his current hell was well=deserved, for Cadmar was not yet strong enough to remove himself from it. Once he was, Cadmar planned to create his heaven, awash in the blood of this filthy creature of the Apostate. And he would continue to build his heaven on Earth. His bricks would be bones and his mortar the very marrow of the creation itself.

The old man spoke of Hell in the after life, delighted in promising Cadmar an eternity of what the Elf already had a bellyful of on Earth. But Cadmar did not believe him. Cadmar was learning that you create your own hell, just as you create heaven, right here, right now. And he believed his current hell was well=deserved, for Cadmar was not yet strong enough to remove himself from it. Once he was, Cadmar planned to create his heaven, awash in the blood of this filthy creature of the Apostate. And he would continue to build his heaven on Earth. His bricks would be bones and his mortar the very marrow of the creation itself.

Of course, I fell in love with The Lord of the Rings, and promptly went to B. Dalton Books and purchased a copy of The Silmarillion, which I still have. When I read the Ainulindalë and Valaquenta, I finally understood Dr. Miller’s warning, and I reconciled with the fact that my Rhyllan myths would never be published in any complete capacity. The one thing I couldn’t understand was why I was unable to make myself change much of anything in my myths, even though their current incarnation would get me chased around by the Tolkien posse.

Of course, I fell in love with The Lord of the Rings, and promptly went to B. Dalton Books and purchased a copy of The Silmarillion, which I still have. When I read the Ainulindalë and Valaquenta, I finally understood Dr. Miller’s warning, and I reconciled with the fact that my Rhyllan myths would never be published in any complete capacity. The one thing I couldn’t understand was why I was unable to make myself change much of anything in my myths, even though their current incarnation would get me chased around by the Tolkien posse.

Five Problems with Social Media

Five Problems with Social Media

21. Do You Have A Personal Phone Line:

21. Do You Have A Personal Phone Line:

51. If You Had The Chance To Professionally Do Something, What would You Do?

51. If You Had The Chance To Professionally Do Something, What would You Do?

On occasion, I have been asked how I get anything done, because it seems I’m doing everything all at once. Well, I am doing everything all at once, but it’s really all about what a person gets used to. It’s also about how a person’s mind works.

On occasion, I have been asked how I get anything done, because it seems I’m doing everything all at once. Well, I am doing everything all at once, but it’s really all about what a person gets used to. It’s also about how a person’s mind works.

Four days and three nights passed before Cadmus’ house went quiet. Out of desperation, Flint had resorted to Vampirising his fellow rats, as he waited for his chance to flee the Plenipotentiary’s lair. It was shoddy cuisine, but desperation made the blood taste much better than it actually did.

Four days and three nights passed before Cadmus’ house went quiet. Out of desperation, Flint had resorted to Vampirising his fellow rats, as he waited for his chance to flee the Plenipotentiary’s lair. It was shoddy cuisine, but desperation made the blood taste much better than it actually did.

Speaking of Jeff Lynne, David Bowie’s unexpected and untimely death made me come to grips with a truth I’ve known for a long time, but never truly verbalised, even to myself. I decided to accept it and to come out, to use the term in a wholly different manner. I wrote Barry Andrews and told him that he was the single most influential individual in my life, more so even than even the godlike Jeff Lynne and JRR Tolkien. I wanted him to know it, in the event either of us kicks the bucket. You should tell people how they affect you before it’s too late. It could be too late in the next five minutes. No one knows what each second will bring. No one.

Speaking of Jeff Lynne, David Bowie’s unexpected and untimely death made me come to grips with a truth I’ve known for a long time, but never truly verbalised, even to myself. I decided to accept it and to come out, to use the term in a wholly different manner. I wrote Barry Andrews and told him that he was the single most influential individual in my life, more so even than even the godlike Jeff Lynne and JRR Tolkien. I wanted him to know it, in the event either of us kicks the bucket. You should tell people how they affect you before it’s too late. It could be too late in the next five minutes. No one knows what each second will bring. No one. I don’t even know what brought it to mind, guessing it had to be some kind of divine inspiration. The long and short of it, though, is that Flint steals the New Hive’s first - and currently only - relic, Cadmus Pariah’s Harming Tree. The story will revolve around Cadmus hunting down Flint, with possible help from Orphaeus Cygnus, and will include the stories and vignettes I have already written about the Harming Tree. As The Blood Crown was essentially a Vampiric Hope & Crosby Road movie in book form, The Harming Tree will be a bit of a book version of a hunt and chase movie, kind of in the vein of Mad Max: Fury Road and the like. I have asked Barry if he could drum up a photo of his harming tree, which is seen only briefly in the ‘Captain Cook’ video, and is obviously the benign inspiration, despite its name, for Cadmus’ dreadful tool of agony. It would be good to have a very clear image reference as I continue this mad journey into the Darkness. I need to jog his memory, though, as it’s been two or three months since I asked him. I’m sure he’s forgotten, and I keep forgetting to remind him. We are old as fuck.

I don’t even know what brought it to mind, guessing it had to be some kind of divine inspiration. The long and short of it, though, is that Flint steals the New Hive’s first - and currently only - relic, Cadmus Pariah’s Harming Tree. The story will revolve around Cadmus hunting down Flint, with possible help from Orphaeus Cygnus, and will include the stories and vignettes I have already written about the Harming Tree. As The Blood Crown was essentially a Vampiric Hope & Crosby Road movie in book form, The Harming Tree will be a bit of a book version of a hunt and chase movie, kind of in the vein of Mad Max: Fury Road and the like. I have asked Barry if he could drum up a photo of his harming tree, which is seen only briefly in the ‘Captain Cook’ video, and is obviously the benign inspiration, despite its name, for Cadmus’ dreadful tool of agony. It would be good to have a very clear image reference as I continue this mad journey into the Darkness. I need to jog his memory, though, as it’s been two or three months since I asked him. I’m sure he’s forgotten, and I keep forgetting to remind him. We are old as fuck.

good news is, this can be fixed! He set me up an appointment for a second oral surgery to basically "sand down" my gums and remove any bone left behind from the first surgery. I will then have to be refitted again for properly-fitting dentures. Thanks to

good news is, this can be fixed! He set me up an appointment for a second oral surgery to basically "sand down" my gums and remove any bone left behind from the first surgery. I will then have to be refitted again for properly-fitting dentures. Thanks to